Oh, jetzt habe ich die richtige Musik für mein

Lieblingsdrink gefunden. Da wird mir sogar bei diesem kalten Wetter warm ums Herz.

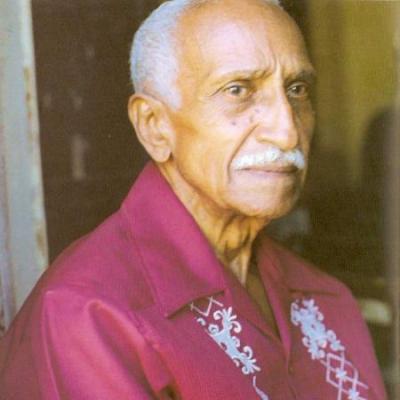

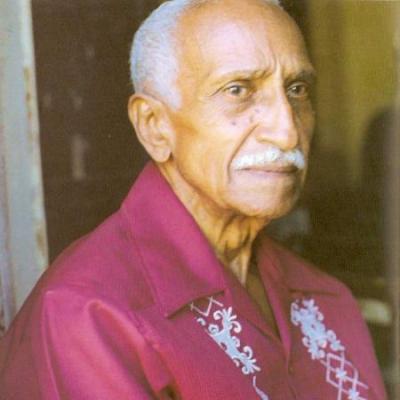

The greatest piano soloist I have ever heard in my life. A Cuban cross between Thelonious Monk and Felix the Cat.

Ry Cooder

Aus dem Booklet

Aus dem Booklet

I was born in Santa Clara in April 1919. By the time I was fifteen I had graduated as a pianist from the Cienfuegos Conservatoire where I studied with a marvellous teacher called Amparo Riso. I lived in Crucijada, a small village north of Cienfuegos, and I’d go once a month to Cienfuegos for my piano lessons. She’d give me music and I’d come back the following month playing all those pieces. She’d say to her other pupils, “Hey boys you all live around the corner and you can’t even learn one piece of music, yet this boy lives in the middle of nowhere and he’s learning twenty pieces a month! So that’s why she kept pushing me up ahead of the other students, that’s why I graduated so young. But I didn’t go into the next phase, which would have been to study to be a concert pianist. I wanted to play Cuban son, that’s what I always loved and still love. As I grew up I wanted to be a doctor, so I studied medicine thinking that music would be my hobby. But people would say “Why on earth do you want to be a doctor if you’re good at music and you’re popular and you have all the freedom in the world! Do you want to spend your life in a lab?” So I gave in.

After playing with groups in Cienfuegos and around the country. I came to live in Havana around 1941 and very soon I began to play with all the major orchestras such as La Orquesta Paulina, Conjunto Camayo, Los Hermanos, Raul Planas and Mongo Santamaria. In short I’ve played with almost all of Cuba! From Camagüey to Oriente but especially in Matanzas and Havana.

In the 1940s there was a real music life. There was very little money in it but everyone played because they really wanted to. Now people play more for money than for the love of it; now there’s more business and less talent. The basis of everything you hear now in Cuban music, that all comes out of that brilliant period.

I’ve been recording for a long time. I recorded with Arsenio Rodriguez around 1943 here in Cuba. Arsenio never studied music but he was an incredible composer. He had beautiful ideas and not just with music but with lyrics too. He was a poet. He never studied music but he knew al lot about ‘heart’. He used to say to me when I first joined his conjunto “Don’t worry about what anyone else is doing. Just play your own style, whatever it is, but don’t imitate anyone. Just carry on like that, so when people hear your music, they’ll say, “That’s Ruben.” I paid attention to him because he was always very intuitive. That’s how it turned out; people have always recognised my playing on recordings or radio.

I left Arsenio’s band to go to Panama with another group, mostly ex-Arsenio musicians. We called ourselves Las Estrellas Negras (The Black Stars) because we were all black. I was the lightest, but that didn’t make me any less qualified! Lili Martinez took over from me with Arsenio. I said to him, “Lili, do you want to play with Arsenio because I’m leaving”. He said, “Hey do you think I’ll be up to it”. I said, of course you will. After that he turned into the best pianist with Arsenio.

I played a lot with the orchestra of Los Hermanos Castro, even though the practised what you might call a kind of apartheid. They always tried to have all white musicians, but Peruchin and I played with them. They had to accept us because of the way we played. Peruchin and I were part of a kind or brotherhood of black pianists and we passed each other work all the time. It was a generation of great pianists and you had to be able to sight read and kind of music straight off, not like now. We’d go into the recording studio or the radio an play stuff we’d never seen or heard before. First time. Perfect.

As for my style, I like the beauty of harmony. I like to make the harmonies rich, not complicated but full. Of non-Cuban pianists I most admire Papo Lucca, because his salsa is very close to son. Son piano is more varied than salsa piano, which is more formulaic and holds on to a single riff for much longer.

After I came back from Panama I joined Senen Suarez’s conjunto and we played at The Tropicana. Then I played with a jazz band led by an Spaniard called Pidre; we played fox-trot, danzon, non and waltz in the big cabarets like the Tropicana. There was still racism, but it was under the surface. When I joined a big band like that, they’d be saying behind my back to the director, couldn’t you find someone a little lighter? And he’d say, but he’s the one who can play the music! Anyway this isn’t any different from any other Latin American country. Ever since the “Discovery”, there’s been racism, and so it goes on…

Finally I became the pianist with Enrique Jorrin’s orchestra, in the early 1960s. Then after he died I took over as director, but I didn’t enjoy the job: I like to leave the gig as soon as it’s over. And now I’m retired. I’ve just turned seventy seven. My main work for thirty years was with Jorrin but I also worked with other bands from time to time like Estrellas de Areito. Jorrin created the cha cha cha. I had already played with him in the early 50s and the cha cha cha happened just after I left the group and by the time I rejoined I had taken off.

Jorrin used to play a lot in a cluib between Prado and Neptuno in central Havana. He used to say that was where the cha cha cha was born, from the way the public would scrape their feet on the floor dancing to that rhythm. So he said “Let’s call this rhythm cha cha cha”. And naturally he was its creator since he was the first to think of it. Afterwards everyone was doing I and Jorrin became very popular. He was one of the most popular Cuban composers ever. It marked the whole era, the cha cha cha. Just as there’d been a period of guaracha, then danzon, the cha cha cha had its moment, ant it was huge. We went on playing other styles, but everyone hat do play that one. That’s how it is in Cuba.

The record came about like this. I don’t have a piano at home any more, so when I saw the one at Egrem studio, I went straight for it and it seems like they noticed what I did. I was playing with the lights off an then they turned them on and I thought they wanted to stop. But they asked me to keep playing so I said to Cachao, “O.K. let’s go for it! What we did is all Cuban music. There are two pieces of mine (though I’m not really a composer).”

From an interview with Ruben Gonzalez by Lucy Duran